Innovative Fitness lived up to its name during the pandemic by launching a digital platform

COVID-19 flattened the business model of many a small and midsize company. But some B.C. entrepreneurs found opportunity in the crisis. Now that the economy is reopening, they’re not going back to business as usual

Curtis Christopherson remembers calling a meeting with his senior staff on Sunday, March 15, 2020. The World Health Organization had declared the global COVID-19 pandemic the previous Wednesday, and the B.C. government had issued a public health order closing, among other things, gyms and personal fitness sessions.

“Human interaction is obviously what we do,” says Christopherson, president and CEO of Innovative Fitness, a chain of 12 personal training studios in B.C. and Toronto. And now it was forbidden. If the lockdown lasted more than a few weeks, the management team realized, the company would lose employees, clients and the community it had painstakingly built up over the years. But what if it tried, at least in the interim, to offer personal training to members using two-way video calls, in their homes?

“Virtual training didn’t exist before COVID,” Christopherson says. Sure, you could join digital fitness classes with Peloton, Tonal or Mirror, but they weren’t personalized and didn’t have the accountability that working with a personal trainer does. Innovative Fitness decided to go all-in. The company continued paying employees for two weeks, during which it trained them in using digital tools. It evaluated trainers’ homes to ensure suitability for offering a professional training session. It hired a web developer, SaaSberry Innovation Laboratories of Coquitlam, to design its own video streaming platform.

Though the whole exercise was a work in progress, a funny thing happened. Seventy percent of Innovative Fitness’s existing clients signed on. They didn’t want to become couch potatoes. Also, their feedback over the ensuing weeks and months indicated that they considered the electronic delivery more convenient than in-person training sessions, and the experience almost as good. When B.C. allowed gyms to reopen—with capacity limits and anti-infection protocols—in June 2020, 56 percent of IF’s clients said they wanted to continue training at home some or all of the time.

Indeed, through word of mouth, the company started picking up clients in Chicago, Boston, Los Angeles, New York. Innovative started signing on new trainers located nowhere near its gyms. The digital platform suddenly freed the organization from any geographical confines.

It dawned on Christopherson that “this was a way bigger opportunity than we thought it was going to be.” He began to see it as a whole different organization, a kind of Uber or Airbnb for personal trainers, wherever they may be. It would eventually transform, with an infusion of $3 million in seed capital, into Wrkout. Now in a “public beta” stage, the digital platform hosted 200 trainers and 300 clients as of early July. “We on-boarded 20 clients in the last four days,” Christopherson says.

Necessity is indeed the mother of invention. Many independent B.C. companies found their business models to be non-starters once people were forbidden from crossing borders or coming into contact indoors. But in their desperate attempt to survive, a few of these small and midsize enterprises, like Innovative/Wrkout, hit upon novel and even lucrative new ways of doing business over the past 18 months. New products, new markets, new delivery technology and processes changed them in ways that will make them stronger, if not ultimately bigger, too.

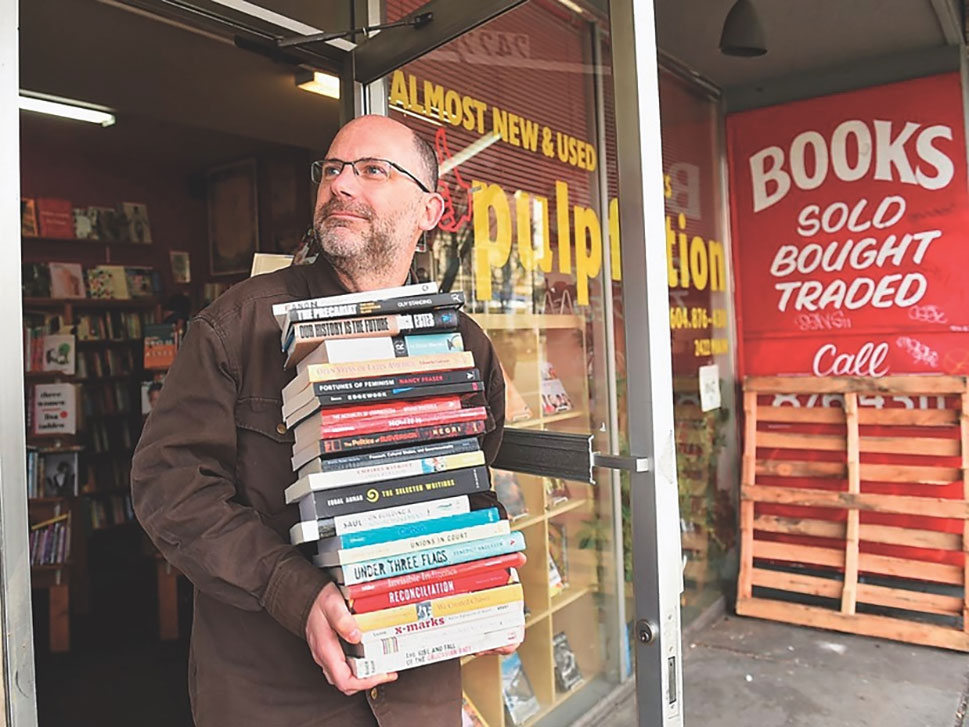

In Vancouver, Pulpfiction Books owner Chris Brayshaw pivoted to online sales

Crisis = opportunity

In some cases, the seeds of these new business models were sown years in advance. When Chris Brayshaw opened his first Pulpfiction Books store on Vancouver’s Main Street in 2000, virtually all his business came from about a 10-block radius, he says. But being in competition with Amazon, he found himself adding services like online payment and home delivery just to go the extra mile for customers.

“It was like building a seawall for a 1,000-year storm,” Brayshaw says of his business tactics before COVID ever arrived on these shores. “I’m a pathological fiddler.”

When the storm did come, Pulpfiction, now with three stores, more than rode it out. Stuck at home much of the time, people were reading more than usual. Brayshaw increased his team of delivery drivers to three and established weekly delivery runs into the Fraser Valley and North Shore and monthly to Squamish.

“Topline sales grew significantly,” he says, estimating that 20 to 25 percent of orders are now made online.

In many cases, small businesses that made pandemic pivots have decided they’re not going back to the old ways. Pre-COVID, Vancouver clothing designer Lexi Soukoreff sold most of her activewear at consumer craft shows across Canada. With the pandemic, the events were all cancelled. “It basically came to a complete standstill,” says the owner of Daub + Design. “We would cater our entire year to those shows. [Now] I’m sitting on thousands of dollars of inventory.”

So how was Daub + Design going to move its product? It did already have a website, though it was until then used for marketing purposes only. Soukoreff upgraded it to take online orders and “dove straight into email marketing,” social media and Facebook ads, she says. She launched a line of infection-suppressing masks just to maintain some cash flow and was gratified to move $22,000 worth of product in their first day.

Toward the end of the year, Soukoreff took a look at a studio space advertised on Craigslist. While some retailers had shuttered stores and focused on online sales, Daub + Design went the other way, taking advantage of a soft rental market to establish a streetfront outlet that opened this June. That meant hiring new staff; Daub + Design now has three in the Vancouver store and two working the digital channel.

Will Soukoreff go back to flogging her wares at craft shows? Perhaps Circle Craft in Vancouver and the huge One of a Kind show in Toronto, she says, but running a store is a full-time proposition; she sees that and online as her main sales channels going forward. “Staying home and having a routine is great. I think my days of travelling every other weekend are done.”

Besides boosting its online presence, activewear retailer Daub + Design opened a Vancouver storefront

Accelerating market shifts

An important consideration for companies forced to fundamentally alter their business models is whether the changes in consumer behaviour wrought by COVID will linger after public health orders have been rescinded. Before the pandemic, Raging Elk Adventure Lodging in Fernie served an international clientele of mostly young budget travellers, sleeping 49 on a single floor.

COVID didn’t force the hostel to completely close—there were still willing guests coming out from Calgary for a few days at a time—but it meant only one customer in a room designed for four, six, eight or even 10—giving the whole establishment a capacity of just six people. Given that each guest now effectively got a private room, the Raging Elk hiked its prices for a night’s stay from $30 to $50, but that wasn’t going to make up for the revenue shortfall.

So staff started researching ways to make the hostel not only compliant with the public health orders then in place but also appealing to travellers wary of infection even after the COVID threat had subsided. They noticed the trend in Japan of self-contained individual hotel pods—smaller and more affordable than a hotel room but with their own electrical outlets, dimmable lighting and so on. In March of this year, the Raging Elk began ripping out the old dorm rooms in time to reopen for Canada Day.

Now there are 24 beds, half as many as before, in self-contained pods. The Raging Elk opted to maintain its private-room pricing. “It is more expensive than a dorm bed, but you get more,” explains general manager Sadie Howse. So far, the guest feedback is positive, and Howse is looking forward to international borders opening in the fall. The real test will be winter, peak season for recreation in Rockies. Howse thinks the private pods will appeal to a slightly older single traveller, in their 30s and 40s, compared to the bunk-bed format.

In Fernie, Raging Elk Adventure Lodging installed Japanese-style hotel pods

Herd immunity

For some businesses, survival wasn’t something they could do alone; they needed their whole industry to make it through. Such is the case in the meetings sector, which depends on businesses and associations continuing to view B.C. as an attractive site for conferences after COVID worries recede.

The grounding of international travel “immediately meant the cancellation of all of our business,” Jennifer Burton says flatly. Her company, Pacific Destination Services (PDS), was a boutique event planning and incentive travel company catering mainly to U.S. companies and associations. After helping clients rearrange previously scheduled meetings in the spring of 2020, PDS staff held a brainstorming meeting.

They decided first to retrain the firm’s event production department in virtual meetings. Later in the year, PDS succeeded in staging a global virtual conference as well as a one-day speakers series. It also drilled down on small-group events for Canadian clients at off-the-beaten-track destinations like Nimmo Bay Resort, Sonora Resort and the Wickaninnish Inn.

But PDS owner Joanne Burns Millar had a bigger ambition: to be part of the solution to the plight the meetings and events industry found itself in. She formed the BC Meetings and Events Industry Working Group, a coalition of event planners, venue operators and service providers dedicated to getting the sector back on its feet. The group worked with the Office of the Provincial Health Officer to create operational guidelines that have since been adopted in other provinces and devised a restart plan for when immunization could permit events to proceed.

As a side benefit of its work with health authorities, PDS was invited to help support vaccination clinics in different health regions. In the Lower Mainland, it helped set up and staff four ongoing clinic sites with parking attendants, patient service reps and other non-medical staff. In the Interior and Northern Health regions, it provided logistics for travelling clinics—everything from community outreach before the road show’s arrival to hiring and stocking trailers to scheduling the nurses’ shifts.

“Corporate road shows are something we’ve done before. There’s never a dull moment,” laughs Burton, PDS’s CEO. And while she doesn’t expect the immunization work to continue beyond the fall, the experience opened doors to government and community work. Though not a profit generator, it has kept the core PDS team of seven together and employed through the pandemic. And the meetings work is showing signs of picking up. Canadian clients are going ahead with smaller events for the second half of the year and American groups are enquiring about 2022.

Proshow Audiovisual‘s business likewise came to an abrupt halt in March 2020. The company used to rent equipment such as projectors and lighting for medical conferences, award shows and fundraising galas. It had 26,000 square feet of warehouse space in Vancouver and Calgary, much of it now empty and inactive.

“COVID reinvigorated us as a service business,” reflects Proshow’s vice-president of production and co-owner, Matt Hussack. Despite the shutdown of events, “people are going to need to communicate,” he and his business partners, Tim Lang and Tim Lewis, theorized. They settled on a strategy to help clients stage virtual meetings with higher production values than your basic Zoom or Microsoft Teams videoconference.

Proshow took the vacant space in its warehouses and set up studio facilities and virtual control rooms. New clients came in the door, such as the BC SPCA, seeking a virtual event to replace its annual fundraising dinner in October, as well as KPMG and the B.C. Automobile Association. Revenue was still down dramatically for 2020, Hussack allows, but Proshow was able to keep virtually all its 50 staff working—indeed, it even hired two more.

With live events now planned for the fall, the company is taking down its makeshift studios to make room for forklifts to move around again. But it will keep its virtual control rooms, Hussack says. He believes some of the meetings that used to take place in person have permanently shifted to cyberspace, with the important caveat that organizations will have to meet higher standards of presentation to maintain the engagement with their audiences. They’ll have to put on a “news-level broadcast,” Hussack predicts.

On a more practical level, COVID forced Proshow to run a tighter ship than before, and those changed processes are going to stick, Hussack explains. The company no longer offers the loose payment terms it did in the past, and the equipment rental business is no longer expected to subsidize staff time spent on pre-production, for example. “We now charge for it,” Hussack says.

Pacific Destination Services, an event planning and incentive travel company, began providing logistics for vaccination clinics like this one in the Interior Health region

What doesn’t kill you

If there’s one lesson every COVID survivor business seems to have learned, it’s to make their organization more resilient in the face of such shocks. “We were set up for one of our better years,” Riggit Services controller Neetu Dhaliwal recalls of the opening months of 2020. But as that fateful March progressed and the concerts and conventions the aerial rigging and suspension contractor had on its books got called off, Dhaliwal realized that Riggit was staring at a 97-percent revenue cliff.

The company’s first reaction was to stop the bleeding by applying for whatever government assistance was available and trimming overhead costs, from cleaning to rent. The company’s 18 core staff agreed to take a temporary pay cut. The best it could do for its hundreds of freelance workers was point them to sources of government relief.

With the vast majority of its business moribund, Riggit dug into the smaller slices of its revenue pie that had cropped up from time to time in past years. It aggressively pitched itself to film and TV productions, which began to pick up after the first wave of COVID infection subsided. It also sought work installing and reviewing rigging in high-school auditoriums, community event spaces and a pharmaceuticals plant under construction. It even helped set up the alternative COVID care site at the Vancouver Convention Centre (never needed, as it turned out).

“We’re not in the business of putting together hospital sites,” Dhaliwal says, but the team was practised at moving into an unfamiliar space and coming up with solutions quickly. In that sense, it was no different from setting up an outdoor concert or in Rogers Arena.

Revenue fell 80 percent in 2020 and will likely be down 65 percent in 2021, Dhaliwal adds. But the core team stayed together, and pay levels were restored earlier this year. In future years, Dhaliwal foresees a more diversified—and larger—revenue base, with more than half the work coming from installations and film and the balance from traditional concerts and events.

“I think it’s made us stronger,” she says of the pandemic experience. “It’s given us confidence in what we can take on.” Riggit wants to be prepared for when any of its business lines shut down—be it events, film or construction. “Going through this again is just not an option,” Dhaliwal says.