For the pioneering industry veteran, winemaking is both a passion and a business–which is why he is moving his newest winery into a converted movie house

“It’s called wine business for a reason,” says Harry McWatters, explaining why he’s converting a former movie theatre in downtown Penticton to a winery. It’s just the latest twist in a distinguished career that spans nearly half a century. In a tough industry, McWatters has succeeded by making the most of opportunities and efficiencies without compromising the quality of his wine.

Today he’s at Local On Lakeshore, a restaurant next to the Summerland Waterfront Resort Hotel on Okanagan Lake, enjoying lunch and a glass of McWatters Collection 2012 Meritage with his daughter, Christa-Lee McWatters Bond. She owns the restaurant with him and her husband, Cameron Bond, and is director of marketing in the family business, Encore Vineyards Ltd. McWatters is controlling shareholder and CEO. His son, Darren, is production manager.

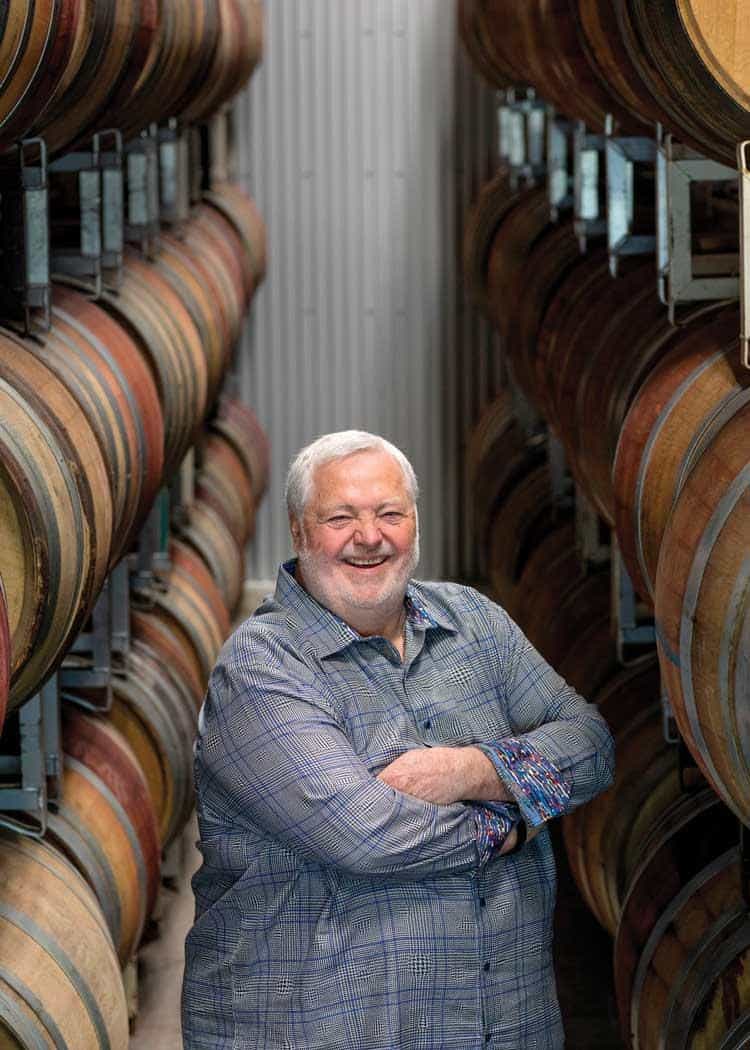

MAN OF THE HOUR

After almost 50 years in the wine business, McWatters brings Time Winery to Penticton

Summerland is where McWatters purchased Sumac Ridge golf course in 1979, turning it into B.C.’s first estate winery. At the time, there were just five wineries of any kind in the Okanagan Valley. “We were the first winery with a restaurant in the country, only because we had a golf course, too,” says McWatters, who turned 72 in May. “The first year I think we did 22 Christmas lunches in 20 days—and I cooked them all,” he remembers. “Christa washed dishes.” He speaks softly, the odd word muffled by music playing in the background, but his enthusiasm for wine and the business of making it in the Okanagan comes through loud and clear.

Summerland is where McWatters purchased Sumac Ridge golf course in 1979, turning it into B.C.’s first estate winery. At the time, there were just five wineries of any kind in the Okanagan Valley. “We were the first winery with a restaurant in the country, only because we had a golf course, too,” says McWatters, who turned 72 in May. “The first year I think we did 22 Christmas lunches in 20 days—and I cooked them all,” he remembers. “Christa washed dishes.” He speaks softly, the odd word muffled by music playing in the background, but his enthusiasm for wine and the business of making it in the Okanagan comes through loud and clear.

Over the following two decades, McWatters brought the term Meritage to Canada and added a couple more vineyards to his portfolio (see “This Is the Life”). Then in 2000, he sold everything except half of his Black Sage Vineyard in Oliver to Vincor International (now called Constellation Brands Inc.), later renaming the 60 acres that he’d retained Sundial Vineyard. “I sold Sumac Ridge because we were made an offer that I couldn’t refuse,” he says, noting that he stayed on for eight years as president of the wine group and vice-president of Vincor Canada.

Last year McWatters, who was born in Toronto and raised there and in North Vancouver, received another irresistible offer. As a result, he sold Sundial Vineyard, where he was building the 25,000-square-foot Time Estate Winery, to Richmond businessman Richter Bai. Instead, Time Winery will be in the 15,000-square-foot former PenMar movie theatre on Martin Street in Penticton, without a vineyard in sight. “When I told Christa-Lee I’m going to accept this offer, she wasn’t real happy with me,” McWatters says. “It took probably a week for it to sink in.”

Although McWatters sold the land, he will obtain fruit from it for several years, as well as contracting with other growers to provide grapes to his specifications. Evolve Cellars, one of three brands produced by Encore Vineyards (the others are Time and McWatters Collection), leases a 13-acre lakeside property in Summerland with a 4.5-acre vineyard, a restaurant, a tasting room and winemaking facilities. McWatters is also looking for land to buy, though not all in one block. “Much as that is a nice thing to have, it doesn’t give us any flexibility we need going forward,” he says.

“It’s confusing, all the things we’ve done,” remarks McWatters Bond. “Who would have thought, Oh, buy a golf course and build a winery’?” So when people ask why they are buying a movie theatre, she replies, “Because he’s always looking at something a little bit different.”

The renovated Time Winery building, which McWatters bought in April and expects to open this summer, will include a complete wine production operation, administrative offices, a wine shop, a tasting bar, a commercial kitchen, a banquet facility, a 75-foot theatre and a 40-seat outdoor patio. Thanks to walk-in trade, he predicts he will sell at least five times as much wine as he would have in the Oliver location.

Just don’t call it an urban winery. Some urban wineries don’t actually manufacture, but “we’re a full-fledged winery,” McWatters says. “We have full crush facilities. But we happen to be downtown.”

And not for the first time. McWatters started his career in 1968 at Casabello Wines, three kilometres south of the new winery. “We never thought of ourselves as an urban winery,” he says. “We were actually at the outskirts of Penticton then, at 2210 Main Street. We did plant some grapes around it, but they were for show more than anything else.”

McWatters points out that a winery unconnected to a vineyard is not unusual. Among others, B.C.’s first winery, Calona Vineyards, is in an industrial area in Kelowna, and California’s Woodbridge Winery, which produces at least five million cases a year, has no vineyard attached to it. And not every winery in a vineyard is a viable business. Of the 272 licensed B.C. grape wineries, in the fiscal year ending March 31, 2017, 95 sold less than 5,000 cases and 65 sold none, according to the British Columbia Wine Institute, which McWatters Bond chairs.

Harry McWatters with his daughter, Christa-Lee McWatters Bond

Consumers are spoiled for choice, she acknowledges, but for people in the wine business, it’s a hard way to make a living. Winemakers need to boost volume or have another job. “In our case, the model is pretty straightforward,” McWatters says. “We’re not going to see black ink for a while, and we know that.” It takes five or six years of aggressive growth to break even because startup costs are high and it’s capital-, labour- and inventory-intensive. “It’s an expensive business, and the biggest money is made in the sale [of the business],” McWatters quips. “We’re not in this just for the money, but we’re sure as hell not in it to not make money.”

Before the Encore management team—McWatters, McWatters Bond and director of winemaking Lawrence Buhler—make a business decision, they ask themselves three questions: will it enhance the quality, will it enhance the brand’s image, and will it enhance efficiency?

“It doesn’t take away from the passion or the romance of what we’re doing; it just makes us a little more efficient,” says McWatters. Encore will always be a small winery competing against the big players of the world, he observes. People will pay a premium for handcrafted wines, but not a $5 premium, and there’s more than a $5 difference between somebody doing 1,000 cases and 100,000 cases, he says. “So we play in that in-between where we can compete with the bigger wineries, giving consistent high quality with greater efficiency than the little guys.”

A prime example is Evolve Cellars, Encore’s third brand, which launched in 2015. “We said, We think there’s a sweet spot in the market here that needs a little more approachably priced entry-level wine,'” McWatters Bond explains. The other two brands, Time and McWatters, target older consumers, although there are plans to change that, with Time aimed at a younger, brand-conscious hipster type. “Our style for Time is a little more Old World, a little more elegant, whereas McWatters is bigger, bolder, more like him, a little more in your face,” says McWatters Bond.

Evolve wines are more like her: friendly, fresh and often bubbly. The price ranges from $15.99 to $30 a bottle, compared to $19 to $35 for Time and $23 to $25 for McWatters Collection. “Smart money says you need to have the volume to get the efficiencies,” McWatters says. Encore produced 13,000 cases in 2016, but how many of each brand isn’t determined until closer to bottling time, when the reds are blended. If a wine doesn’t fit the profile of Evolve, Time or McWatters, it’s sold as bulk product.

“Even Evolve, our market entry-level [brand], I’m not going to compromise the quality of that,” McWatters Bond says. “So we sell our pressings; we sell anything that doesn’t fit within what our brand essence is for each of the brands. But we look at opportunities first and foremost. We talk about it.”

Not every decision relies solely on the business case. McWatters plans to produce a port-style solera, a style of wine he particularly likes. Apart from vintage ports, the market has shrunk, partly because the terms “port” and “sherry” are restricted to products from Portugal or Spain. Since the category isn’t growing, it’s been overlooked. “If you look at the business model, nobody would say, I want to be a port or a solera producer,’ because it’s a tiny market,” he says.

The market for sparkling muscat, however, is one of the fastest-growing in North America, according to McWatters. As a judge at three or four wine competitions in the U.S. every year, he’s noticed how large the category is and how many medals it wins. “So that’s one where the business case is going to drive what we’re doing,” he says. “What we’re going to do with our port style and sherry style, the business model says, Don’t do it.’ It’s a shrinking category, but nobody’s doing it here, so there’s an opportunity for us to develop a niche.”

The McWatters ventures continue to evolve, like the province’s wine industry, whose sales grew from less than $7 million in 1992 to $254.5 million in 2015, according to the B.C. Wine Institute. “There’s nobody in the business in British Columbia that was here when I started,” McWatters notes. “Less than half the people were here 10 years ago, so we’re an industry under huge growth.”

Some of the more established winemakers are now seeing their children get into the business. McWatters encouraged his own children to try something else, he says, “because this is a lot of hard work, and it’s my dream. You can’t come into it and wake up when you’re 30 or 35 years old and realize you’re in the middle of your dad’s dream. But there’s a magnetism about the lifestyle and the region that brings them back. It’s the kind of industry that becomes an obsession.”

A taste of 9 wineries in the South Okanagan