Plenty of Fish | BCBusiness

Local online dating phenom Plenty of Fish, built for the web, thinks it can survive and grow in the mobile age

He’s responsible for thousands upon thousands of marriages, earning millions upon millions along the way. Yet Markus Frind’s success can be boiled down to a simple formula. In 2003, when dating websites were paywalled, the founder of Vancouver-based Plenty of Fish (POF) offered a free alternative by keeping costs low and leaning heavily on ad revenue. For years, Frind famously claimed to work only an hour a day, watching the money roll in as POF swam past the competition and grew into one of the world’s most popular dating websites.

But gone are those simpler days.

“Everything you used to do three years ago has tripled now,” Frind says. Or more than tripled: five years ago, POF counted just three people on its payroll, while today the company employs 80. As a result, the CEO’s one-hour workday has given way to “half a day” of labour. Yet while revenues have also risen in recent years—including this one, which Frind expects will outperform 2013 by 30 per cent—the mass-market adoption of smartphones threatens to roil the waters for POF.

Despite the popularity of the company’s iPhone and Android apps (second only to Tinder, an explosively popular “hook-up” app), Frind’s old revenue model—that once-simple, web-based formula—is under siege, as advertising doesn’t work well on the smaller screens of smartphones. Meanwhile, POF’s chief competitor is a veritable whale by comparison: New York-based IAC owns popular sites OkCupid and Match.com, the online dating leader in terms of revenue, and now Tinder.

You’d be hard-pressed to find an industry more upended by the mobile revolution than online dating, and like that first fish out of water, POF will need to evolve to survive. Frind says that for people under the age of 35, a whopping 90 per cent of POF’s visits now come from phones rather than web browsers: “Web is not something that really has a future. Everything’s mobile.” Already Frind has almost everyone at POF updating and improving the mobile apps—while only a single developer still monitors the website.

Despite the dominance of mobile in terms of visits, Frind says up to 60 per cent of the company’s “tens of millions of EBITDA” still comes from its website. In terms of advertising, “you’re selling stuff for five cents a click” on mobile, he says. POF’s apps therefore make money from upgraded memberships (users can pay a monthly fee for extra features, such as the ability to add more photos). Frind is the first to admit monetization on mobile has a ways to catch up. “Certainly,” he says, “it’s not equal to desktop yet.” And while overall revenue is hitting all-time highs, this year the number of people visiting the website began declining for the first time ever. In fact, IAC’s free dating website, OkCupid, has caught up with POF on desktop according to web data firm Alexa (both are top-500 websites globally).

Mark Brooks, one of the Internet dating industry’s few consultants, says that while Frind will never have the deep pockets of IAC, POF’s mobile numbers are promising. Now he just has to figure out how to make mobile visitors as valuable as its declining desktop ones. Brooks points to online classifieds behemoth Craiglist for inspiration. “Most people think it’s entirely free,” he says, “and it is—except for people who want to advertise jobs, and they make a lot of money from that.”

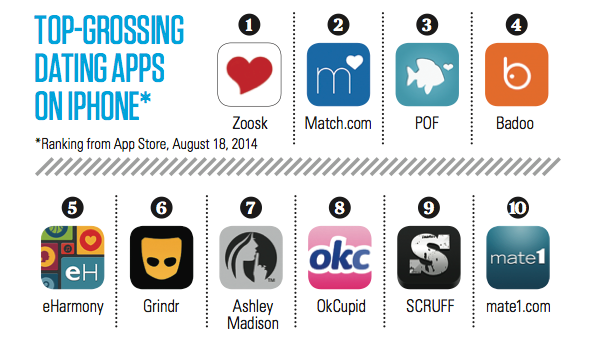

For POF, this could mean finding ways to increase the number of users who upgrade to a paid account. For example, Zoosk, the top-grossing dating app (apps with the highest total revenue) on iPhone, charges users who want to send someone more than a single message. That said, Frind’s priorities lie elsewhere at present. “Mobile is pretty much a land grab right now,” he says. “Grab as many users as you can, then figure out what to do with them.”