Kitsault, BC | BCBusiness

In 1980, the prefabricated town of Kitsault was hastily erected beside a significant deposit of molybdenum in a remote, idyllic stretch of coastal northern B.C. to house and service 1,200 miners and their families. Two years later, molybdenum prices tanked and the town was abandoned. In 2005, a Virginia businessman bought Kitsault, sight unseen, as a future eco-retreat that would attract the planet’s best and brightest to think and create in beauty and serenity. But then molybdenum prices bounced back and that’s where our story begins…

My visit to Kitsault unfolds like a B-grade horror movie: on an unnaturally dark August day, a naive writer drives alone through wilderness and fog to reach a remote ghost town forgotten by time. The town is completely intact, right down to manicured lawns and paved roads, but there appears to be no one there. The doors to every building are open, so the slightly jittery scribe decides against better judgement to explore the town, just as the sun dips behind verdant mountains that close in around the town like a wall.

I’ve come to explore one of B.C.’s last prefabricated “instant” resource towns, built in 1980 to house 1,200 miners and their families right next to a huge deposit of molybdenum. Two years after the company invested $250 million to build the town and restart the mine about 140 kilometres north of Prince Rupert, molybdenum prices crashed and Kitsault was abandoned to local moose and black bears. A solitary caretaker remained, keeping the heat running to prevent the houses from returning to the earth. The town remained vacant for the next 23 years, while a succession of mining company owners, ever optimistic, waited for molybdenum prices to bounce back.

The boom-and-bust story of Kitsault took a strange twist in 2005, when a wealthy Virginia businessman saw a newspaper story about an unusual town for sale, complete with a curling rink, pub and 300 detached and apartment homes, frozen in the year 1980. Without setting foot in the town, India-born, Carleton University-educated Krishnan Suthanthiran bought Kitsault sight unseen. The asking price was $7 million. (“Krish” as he is known, who runs an international medical supply business, likely paid far less, though he declines to specify how much.) Suthanthiran soon launched a website branding the town as “Heaven On Earth,” exalting a vague vision of Kitsault as an eco-retreat and refuge for the planet’s best and brightest – scientists, philosophers and artists – to think and create in peace and quiet.

Just as his vision was taking shape, the price of molybdenum – the mineral Kitsault was created to exploit – began to surge, and the big molybdenum deposit just over the hill from the town, long ignored, began to attract new excitement. Enter Avanti Mining Inc., a Vancouver-based junior mining company that bought the mine and surrounding mineral tenures for $20 million in 2008. Through much of that year, molybdenum prices remained at historic highs of over $30 a pound, further sweetening what appeared to be a winning prospect.

Disagreements about Avanti’s legal right to access the town came to a head almost immediately, sparking years of legal conflict that continues as of this writing, pitting two very different visions of northern development against each other. One is a molybdenum mine that promises to keep hundreds of people well paid for 15 years, the other a business that will draw on eco-tourism and preserve the area’s pristine natural beauty in perpetuity, minus the employment boom and corresponding surge in government tax revenue. The question now is, can the town and the mine, created for the same purpose more than three decades ago, today pursue separate paths?

Image: Chad Graham

Kitsault’s apartment block.

About a two-hour drive north of Terrace, the smooth Nisga’a Highway transforms into a rough wilderness road, which snakes for nearly 90 kilometres through blasted rock and swamp, emerging finally to meet the ocean at Kitsault. Reaching the end of this road intact in an economy rental car, I soon discover that Kitsault is not completely deserted. Shortly after my arrival, I’m intercepted by a big blue pickup truck driven by Indhu Mathew, who manages the town with her husband on behalf of the absentee owner. A power window slides down, shattering the horror movie vibe: her smile is radiant, her crimson nails immaculate and there’s a toy-sized yappy dog sitting on her lap.

I follow Mathew to her residence. It’s the best house in Kitsault, formerly the home of the mine manager, and is built on a promontory with a stupefying view of a mountain-ringed fjord called Alice Arm. “It’s really paradise here,” she tells me as we sip tea while looking over the water. There are at least seven black bears that call the town home and Mathew woke this morning to find a moose on her lawn. “We’ve got the animals, mountains and the ocean,” she says. “It’s quiet here.”

She oversees a skeleton crew of five men who work full-out five days a week to prevent the rainforest from reclaiming the town. It’s just part of the $1 million that Suthanthiran spends on Kitsault each year, not including the pending costs of overhauling the water system and replacing roofs in a climate where up to 300 cm of precipitation falls annually. Power and heat alone consume $15,000 a month.

Mathew is currently preparing for a Christian retreat that will begin the week after I leave, when 60 people will either charter a float plane to Alice Arm or drive the wilderness road, staying in one of the apartment complexes (there is currently capacity for 200, but it will eventually be 1,000). It will be the third conference that has been held here in the last three years, even though the final vision for the resort remains in a sort of limbo. The usually media-shy Suthanthiran tells me by email that the economic crash of 2008 has forced him to scale back his spending, not only for Kitsault, but for the many other interests he continues to pursue outside of his company. “Our first goal is to restore and maintain the town from the poor upkeep of the past 25 years,” he says. “Kitsault has many possibilities. Our goal is to begin to add more staff and bring [more] visitors next year.” What Kitsault will certainly not be, adds Mathew, is a place for loud, gas-powered toys like quads – possibly a veiled reference to Avanti’s proposed 40,000-tonne-a-day milling operation just over the next mountain.

[pagebreak]

Image: Gayleen Whiting

The Silver City

Constructed for a reported $50 million, Kitsault is built on multiple levels: there is an expansive, flat stretch of land on its shoreline, with a steep road that leads to a plateau of houses and empty foundations and a third level with multiple apartments, as well as amenities such as a shopping centre, pub, community centre and school. An earlier mine that was in production between 1968 and 1972 had established the existing layout of the town, but most of those buildings had to be demolished after the water was left on one winter.

Before that Kitsault had been known as Silver City and was the site of cottages built by the families that worked at the Dolly Varden silver mine just across the fjord in the town of Alice Arm, where 2,000 workers and families once lived. Just down the coast is Anyox, another mining town, which went under during the Great Depression. Today the closest road-accessible supply centre is Terrace, about 200 kilometres away; Prince Rupert is 140 kilometres down the coast, accessible only by air and sea.

A melancholy hangs in the air here; everywhere there’s evidence of lives turned upside down, apparently overnight. Most striking is the hospital. In the waiting room, a 1983 Maclean’s magazine cover story profiles René Lévesque and highlights the Quebec sovereigntist threat. An unsettling visit to the operating room reveals rib splitters and all manner of operating tools, still shiny and apparently unused.

Up the street is the huge Maple Leaf Pub, which looks like it could have been shut down mere weeks ago, except for a placard that advertises smokes for 70 cents a pack and gum for 15 cents. The shopping mall, too, is a wonder: grocery store, post office and a Royal Bank branch with the empty vaults wide open. The community centre, which was opened by mine owner Amax Canada president John Foreman with great fanfare in 1982, still stands: “The mine will be one of the most competitive of all molybdenum mines as time goes on,” Foreman told gathered Kitsault residents at the time. “For people here, Kitsault will become a model town, a model community for the long term.”

Image: Chad Graham

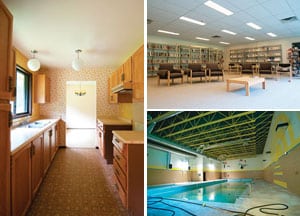

A kitchen devoid of appliances (left), the town library

(top right) and lockers in the community centre the

community pool.

It’s near midnight when I return to my apartment, a ground-floor suite in a huge block of 40 apartments on three floors; at one point during the night I consider propping a chair under the doorknob of the front door, an irrational urbanite’s reaction to the fact there’s absolutely no one outside. The next morning it’s all brilliant blue sky and sunshine, revealing the true height of the surrounding mountains. A moose forages in a distant eelgrass bed at the end of Alice Arm. Suthanthiran’s branding tagline “Heaven On Earth” doesn’t seem so far-fetched today.

As I continue exploring, a thought continues to gnaw at me: why would a company go through so much effort and extra expense to build a shopping mall, curling rink and all the rest of the amenities that are completely secondary to the mine? I find an answer at the Kitsault museum, a two-floor bungalow that contains the artefacts gathered by the Mathews as they combed through the town. (A huge black bear is about 10 metres from the front door as I walk up the stairs, but fortunately he is more interested in eating grass than in me.) A sepia-toned March 2002 article in the short-lived Kitsault Times newspaper explains why Kitsault was built: the “major problem with northern mines is high employee turnover,” reads the article: in excess of 100 per cent per year in the B.C. north. Interior B.C. mines further south have a much better record of retaining employees. “Clearly the difference is the isolation factor. To compensate for this, employees must be provided working and living environments that are conducive to long-term stability.”

Creating stability for Kitsault meant ensuring that at least 70 per cent of the mine’s employees were married – ideally with kids. To retain families, the company offered “recreation and shopping,” school up to Grade 8 and home-purchase plans that included guaranteed buy-back provisions. The company also invested to complete the last 32-kilometre section of road built through extremely rough, mountainous terrain, enabling access to the closest supply centre of Terrace.

Amax Canada looked for employees like John Watson, who was 23 when he came to Kitsault as a heavy-equipment operator. He initially came alone while his wife and two infant boys remained in Smithers, he tells me from Smithers by phone. That changed quickly when the company moved the Watsons into a house just down the hill from my apartment accommodations. Like many other Kitsault residents, Watson treasures the time he spent there. He remembers a place where five feet of snow could fall in a single night and nearby rivers ran thick with big coho salmon. “I loved the place; I really did,” says Watson, who went on to drive logging trucks, and is based in Smithers today.

The town fulfilled its primary function of retaining employees: most stayed until they were forced to leave. Watson recalls October 1982, when it all came crashing down: “It was a kick in the teeth, really,” he says. “They told us there would be a 25-year life span for that place and it closed down in three years.” The exodus from Kitsault was slower and less melodramatic than one may think: it took a full six months for the town to completely clear out.

Watson remembers big, anxious meetings between the townspeople and company, and that many workers were given a chance to go to Houston and other mining towns. Now 55, Watson has heard all about the Kitsault mine potentially reopening. “I’d never go back in there again,” he grumbles. “My life is set up in Smithers now and it’s way better this way.”

Avanti’s mining camp is a 10-minute drive from the town site and is nearly as deserted as the town. I’m greeted by Denver-based president and CEO Craig Nelsen who, in khaki pants and bright white New Balance sneakers, could easily pass for any of the American tourists who flock to the northwest each August for sport fishing. (As it happens, Nelsen is booked at Haida Gwaii’s Langara fishing lodge the day after our interview.) He points to a long trailer, which can accommodate 50 workers and is expandable to 150 – big enough to get the company started for the initial phases of mine construction, he says.

Nelsen is friendly, but doesn’t suffer fools gladly: he doesn’t like being interrupted with supplementary questions as he explains Avanti’s vision and he fills my ear about how the federal mine-permitting approach needs to change. He is also candid about the biggest challenges facing his proposed mine: in particular, on-land storage of tailings and the access road, which needs to be passable year-round to bring his workers in and drive his molybdenum out. Both of these issues stem from the truly awesome quantity of precipitation that falls here, mostly as snow during a winter that typically lasts eight months. (Avanti’s camp lost power six times due to weather-related issues last winter alone.)

Both of the previous Kitsault molybdenum operations disposed of mine tailings in the ocean, the first by dumping waste into Lime Creek, which runs through the town of Kitsault, and the second using a conveyor to move its tailings into Alice Arm. Disposing of tailings in the ocean so incensed the Nisga’a First Nation that they picketed Amax’s AGM in New York City. “Amax is not a company that commits nearly $200 million to a project that is environmentally unacceptable,” John Foreman later told the Vancouver Board of Trade, about seven months before the Kitsault mine closed. “I can assure you, we wouldn’t be in business today.”

Avanti’s relations with the Nisga’a First Nation, whose vast Nass Wildlife Area created in their 2000 treaty includes the Kitsault mine, are certainly better than with previous mine owners, even though Nisga’a Lisims Government president Mitchell Stevens would not confirm in an interview whether or not the Nisga’a support the Kitsault mine.

My talk with Nelsen turns to the global economy and the slowing of Chinese economic growth. He says the economic situation in Europe is “very disconcerting,” but notes that China, even though it has a lot of molybdenum mines, is a very inefficient producer. With molybdenum officially designated by the Chinese as a metal of “strategic interest,” they are often willing importers whether they are ready to use it or not.

I later discuss the historic volatility of molybdenum prices with Nick Carter and what it means for a mine like Kitsault. Carter is a former B.C. government geologist who has worked in the private sector for many years and arguably knows more about this metal than anyone else in B.C. He first came to the Alice Arm mining district in 1964 as a young B.C. government geologist specifically to scout for molybdenum and says molybdenum prices can be more volatile because it is not as diversified in its uses as other minerals. “You can get into an oversupply situation pretty damn quickly,” he says.

Carter says it was a rise in molybdenum prices that convinced the U.S. copper giant Kennecott to open the first Kitsault mine between 1968 and 1972. A similar rise enticed Amax to build Kitsault and reopen the mine from spring 1981 to October 1982, when a recession dragged prices back down. In early 2008, the same year Avanti bought the mine, molybdenum stood at more than $34 a pound – only to drop to about eight dollars by February 2009.

Viewed through this historical lens, betting hundreds of millions on a 15-year high and sustained price for molybdenum may resemble casino gambling. “It’s tough to do financing even on a gold prospect in this province right now, but molybdenum? Forget it,” says Carter. “It’s one of those periods where it’s gone away for a while.”

[pagebreak]

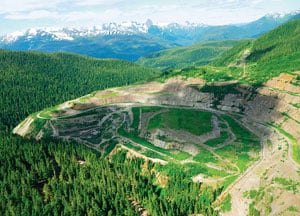

Image: Christopher Pollon

The Avanti mine.

An ‘Instant Town’

There was a time, not long ago, when the common belief was that B.C.’s north would be populated one pop-up resource town at a time. It was a time before the advent of the fly-in, fly-out resource camp, where workers are brought in for a typical two-weeks-on, one-week-off work cycle. In the case of Avanti’s proposed Kitsault mine, there is no need for a town equipped with amenities for families: buses are planned to pick up employees in Terrace and drive to the mine; workers will then make the return trip two weeks later for one week of down time before starting the cycle again. The same resource-camp cycle would apply for at least eight proposed mines in the remote northwest corner of B.C., which will have access to cheap grid power after 2014, courtesy of the northwest transmission line, which has already broken ground.

Yet, as recently as the 1960s, the B.C. coast from the tip of Vancouver Island to the mouth of the Portland Canal was still home to dozens of tiny resource settlements, populated by entire families, sustained by salmon canneries, forestry operations and mineral deposits. Kitsault itself was part of a post-World War II wave of “instant towns” like Mackenzie and Tumbler Ridge, which focused more than ever before on creating a social environment conducive to family life, in contrast to the more spontaneously created company towns that existed earlier.

Rudy Nielsen, who has been at the helm of NIHO Land & Cattle Co. for nearly four decades, has seen many of these towns come and go and has bought at least eight of them. Beginning in the early ’70s, Nielsen built a profitable business buying up intact, abandoned B.C. towns – forgotten resource outposts like Nashville, Fergusson and Sheep Creek. He carved them into lots and sold off the parcels cheap, mostly as recreational properties. When he first caught wind of Kitsault in 2005, he initially planned to buy it and subdivide it the same way. (His subsidiary company LandQuest Realty ultimately sold it to Suthanthiran instead.) Nielsen says Kitsault ended up being different: it was the first time in B.C. history, to his knowledge, that a single owner bought up a town not to subdivide, but to keep intact.

Nearly eight years after his purchase, Suthanthiran’s plans for the town remain unclear, although he says his commitment to the town remains strong. Over the next six months, he will sell four properties, generating about $12 million. “Once I refinance my current loans, I can focus constructively on all my projects, including Kitsault,” he tells me by email.

Image: Christopher Pollon

A wall of pure molybdenum.

Meanwhile, legal action between Suthanthiran’s Kitsault Resort and Avanti Mines continues. Avanti won a 2010 B.C. Supreme Court case that confirmed the existence of Avanti’s right of way through the town, which had existed historically back when Kitsault was a mining town. Instead of appealing the 2010 decision, Kitsault Resort’s legal team commenced a new proceeding in September, seeking to have the right of way cancelled. A summary trial should be heard within 12 months, although potential appeals could go on after that.

The case is “new legal territory” says Gavin Crickmore, a lawyer with Vancouver’s Hungerford Tomyn Lawrenson and Nichols, which is representing Kitsault Resort, because the right of way was originally granted when the town and mine were under common ownership. When Kitsault Resort bought the town site, there was still no conflict because at the time the mine had been reclaimed and the right of way was used for water monitoring that was beneficial to the town. The problem now, says Crickmore, is that Avanti has interpreted the right of way as providing unrestricted access and use of the town site for any purpose. He says Avanti currently lands helicopters at various locations on the town site, ignoring a single location designated by the resort. The right of way “is incompatible with what the town site has become – a unique and special treasure,” says Crickmore.

Avanti’s Nelsen is adamant that the town was created to service the mine, a claim Avanti’s 2010 court victory vindicated by confirming that Avanti’s right of way through town continues to exist. He says that for Suthanthiran, it’s a case of buyer beware.

Conflict also continues over potential mine impacts on the town. A June 2012 consultant report commissioned by Suthanthiarn says Avanti has not adequately considered the impacts on the town, including potential ground and surface water contamination from tailings leakage and acid rock drainage. “The location of the [tailings] dam is a huge concern to us,” says Matt Mathew, Indhu’s husband and town steward. “God forbid if something happens, it will all run through the town.”

The B.C. Environmental Assessment Office confirmed that its staff have visited the town of Kitsault and that it has asked Avanti to respond to the resort’s concerns. It is also currently working to set up a meeting of both parties, which has yet to occur as of mid-October.

As the end of my visit to the mine approaches, I have saved my most important question for last. Can a mine and the Kitsault resort coexist? Nelsen assures me they can. Later, by email, Suthanthiran dismisses the question outright. “Right now we have not seen a bona fide, realistic project or one with the financial resources to carry out a long-term project other than us moving forward as we have done for the past six to seven years.” The only certainty now is that the battles will be fought behind the scenes, through the B.C. legal system and using the B.C. Environmental Assessment Office as potential intermediary.

My thoughts return to the long road back to Terrace – and my own troubles that are just beginning. The fog has returned, descending from the mountains onto the hauntingly beautiful, desolate rainforest. I have to drive back to civilization alone through the same snaking, ungraded horror show of a wilderness road I barely made it through on my way here.

“We’re an open book,” says Nelsen as we shake hands and part ways. “We’ve got nothing to hide up here and we’ll talk with anybody and everybody.” He smiles and wishes me luck on the drive back to civilization.